Bidston

By Kenneth Burnley

Extraction from the book "Portrait of Wirral" (1981) reproduced with permission

![]()

|

The western limit of Birkenhead town proper

is clearly defined physically by the hill ridge which extends roughly

north-south from Bidston to Storeton. Birkenhead’s housing, however,

knows no such physical barriers, and the town’s suburbs have

inexorably spread across the ridge and down into the Fender Valley

beyond, subrnerging once-rural villages in a tide of bricks and

mortar. A hundred years ago Birkenhead’s more prosperous residents, viewing with alarm the spread of industry’s noises and smells to their own doorsteps, took to the hills and erected palatial residences set amongst pine woods and heathland. These high-class suburbs of secluded mansions, within easy reach of Liverpool and Birkenhead, but far enough away for their owners to forget about their place of work after hours, are now sandwiched between Birkenhead town on the one side and high-density council housing estates on the other, and as such are an attractive buffer between the two. Although many of the older residences have been demolished and “luxury flats” built in their place, much of the area retains a strong country atmosphere, enhanced by large areas of public open space such as Bidston Hill, which is as good a place as any to start a description of the area. Mention of Bidston Hill conjures up, for me, fond memories of long childhood hours spent playing in its woods, picnicking on its springy turf, and hiding in its secret places. And, always, the feeling that this was no ordinary place. And indeed, few other parts of Wirral can offer so much of interest in such a small area. Where else in a few hundred acres can you find open, gorse-covered heathland with fine land and seaviews, pine woods and rhododendrons, a lighthouse, an observatory, a Windmill, rock carvings, and a fascinating seventeenth century village? |

|

|

Bidston Hill’s unique history begins in 1407, when the top part of the ridge was enclosed for use as a deer park by the lord of the manor. Parts of the enclosing wall, known as the “Penny a day dyke” (left) because of the rate of pay of the men who built it, still survive today, albeit in a rather neglected state. During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries a number of farms sprang up on the hillside below the wall, followed in the late nineteenth century by large houses built for Liverpool merchants and shipowners. The top of the hill, however, still owned by the manor of Bidston, remained untouched, used only by Walkers. In 1893 local residents, fearing the eventual development of the whole area, urged the corporation to purchase the remaining land, and as a result 141 acres were acquired for public use over a period of twenty years. Most visitors to Bidston Hill are attracted in the first instance by the windmill, which is a prominent landmark for miles around. This mill replaces earlier, Wooden peg mills which occupied the site as early as the mid-sixteenth century. Evidence of such a mill can be seen about twenty yards north of the present mill, in the remains of the base trenches and a circle of small holes Where the tail-piece was wedged. Similar tread-holes can also be made out close to the wedge holes. The present mill, a tower mill, was built after the previous wooden mill had been destroyed by fire in 1791, caused by friction from the sails revolving at high speed during a gale. Harry Neilson, in his Auld Lang Syne, recounts milling life a hundred years ago: I distinctly remember a walk over Bidston Hill when a child with an elder sister, about the year 1868. A fresh breeze was blowing and the sails of the mill were turning round in full swing, grinding corn. A cart, laden with sacks of flour, stood just ready to leave by the stony cart-track to the road below While the miller stood by chatting to the carter. As we stood watching, the loaded cart moved off and the miller asked us if we would care to look inside the mill. His invitation was gladly accepted and in we went. |

|

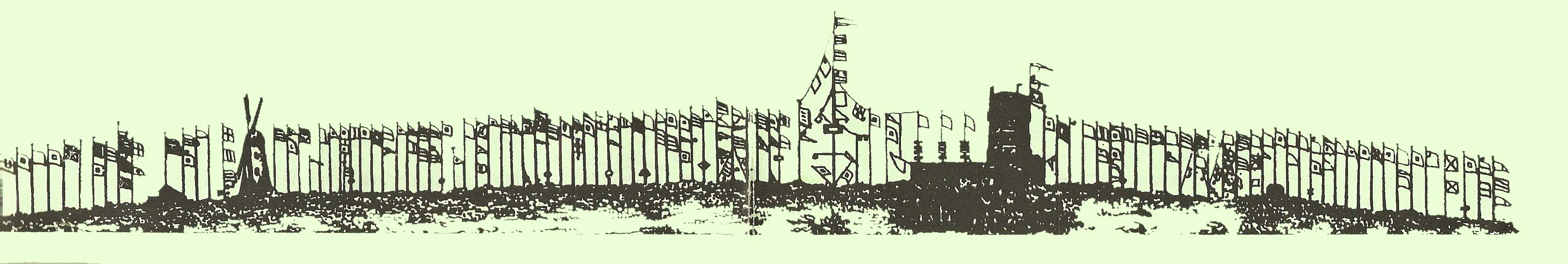

My first and lasting impression was of the

loud buzzing noise of the machinery, very like the sound of a swarm of

angry bees but much louder, and my next, the whiteness of everything

inside the mill, caused by the coating of fine white flour dust which

nothing could escape, not even the miller himself. Neilson goes on to recount how one of the miller’s predecessors had been killed by one of the great sails striking him on the head as he stepped out of the mill one dark night, and also how a mischievous youth had daringly grasped one of the sails as they were revolving and had been lifted high up into the air before the sails could be stopped! This mill, too, has suffered damage by fire several times, as well as structural damage caused by the severe gales which frequently blow on this exposed ridge. Milling ceased about 1875, but the mill has been restored and reconditioned several times since, and is in a fairly good state of repair. Stand beneath the massive sails on a blowy day, and picture the scene as it may have been 150 years ago, the great sails racing round, the machinery humming, and cartloads of flour trundling down the track to be made into bread at the local farms. It is a short walk along this rocky ridge to the Observatory; much has been said about the view from here Which, although extensive, is certainly not “unrivalled in Cheshire”. It is, if anything, depressing. Urban sprawl in every direction reminds us of the changes which have taken place in this part of Wirral over the years; only far away in the south-west do bricks and mortar, motorway and flyovers, give Way to green fields. Nearer at hand, a number of circular holes, set at regular intervals into the rock along the ridge, are a reminder of a unique signalling system employed here over 200 years ago. In those pre-radio days, Liverpool shipowners were able to receive advance notice of their ship’s homecoming by the sight of a flag hoisted on the appropriate flagpole. Of the 58 poles on the hill at that time, 49 belonged to Liverpool shipowners, the other 9 being used for sending advance warning of the approach of warships. |

New roof being added to the Mill |

|

|

|

Unfortunately, such notice Was often too

short to be of much use, and in 1827 the system was extended to

Anglesey so that news of a ship’s approach as far away as Holyhead

could be sent. This was achieved through a series of nine signal

stations along the North Wales coast, each station having a semaphore

system by means of which almost any message could be conveyed. The

first message sent on the system,announcing the sighting off Holyhead

of the American ship Napoleon on 26th October 1827, took fifteen

minutes to travelthe seventy-two miles to Liverpool. Eventually,

shorter messages took much less time to transmit, the fastest recorded

time being only twenty-three seconds; the average message took eight

minutes. Some idea of the importance of Liverpool as a trading port in

the mid-nineteenth century is gained by the fact that some 1300

vessels were “on tap” to the system of the time. The semaphore system turned out to be short-lived, for by 1860 a cable had been laid between Holyhead and Liverpool, eliminating the obvious problems of using the semaphore in foggy weather. Bidston I-Iill has been closely associated with Liverpool’s shipping in other ways too. The Observatory (now the Institute of Oceanographic Sciences) at the extreme northern end of the hill was built in 1866 to assist in the accurate setting of ships’ chronometers before a lengthy sea voyage. This was done using accurate observations of the sun, moon and stars, a job which was originally carried out in a building at Waterloo Dock in Liverpool. Observing conditions there, however, deteriorated due to the atmospheric pollution from the city’s chimneys, and the equipment was moved to Bidston where the air was comparatively cleaner. Weather predictions for local shipping were also a feature of the Observatory’s early days. Over the years, 'the Observatory’s work has gradually changed and developed. In between the more “routine” tasks of weather forecasting, tide predicting, and measuring land movements, the Observatory has undertaken the measurement of the width of the Atlantic Ocean and the firing of the “One o’clock gun”. (right) |

|

The view from the semaphore post positions |

|

|

The latter was a loud time-signal fired each

day from a cannon at Birkenhead Docks, the electrical impulse being

transmitted from Bidston. The gun could be heard over a wide area, and

was used by many Birkenhead and Liverpool Workers as the signal for a

return to work after their lunch break. The gun was fired for the last

time in 1969. Perhaps the Observatory’s most celebrated achievement

was the inventing and perfecting of the tide-predicting equip- ment. This brilliant mechanical calculator, a forerunner of today’s computers, was able to predict, with amazing accuracy, the height and time of high tide anywhere in the world for any particular date past, present or future. Although now superseded by sophisticated computerised equipment, the original machine, together with the original telescopes from the observation domes, are carefully preserved and on view in the Liverpool Museum. . Cheek by jowl with the Observatory, and seemingly miles from the sea which it served, Bidston lighthouse remains as a reminder of the days when, together with its partner at Leasowe, ships entering the Mersey had to line up the two lights to ensure a safe entry through the narrow channel. The first light here was built in 1771, to replace the original “lower light” at Leasowe which had been washed away; Bidston thus became the “upper light” of the pair. The original building at Bidston was “a substantial stone building with an octagonal tower, which from a distance had the appearance of a church”; it was pulled down when the Observatory was built in 1866. The present lighthouse was built 1872-3 but the light has not shone since 1908. |

|

|

A keen eye. on Bidston Hill will soon search out other, less obvious, features of interest. The rock carvings, for example. On a flat sandstone outcrop near the Observatory are several carvings of figures a “Sun Goddess” with outstretched arms whose head points exactly to where the sun sets on Midsummer’s Day; and a cat-headed “Moon Goddess” with a moon at her feet. Another outcrop bears the figure of a horse. Who carved these, and why? No one is sure, but a date of about the second century has been tentatively suggested. A circular hollow cut into the sandstone on the top of the hill behind Bidston Hall is said to be the remains of a cockpit, used by villagers taking part in the cruel but popular sport of cock-fighting. |

|

Most of the cottages which at one time were

scattered about the slopes of the hill have gone. A few, however,

remain; and one in particular has an interesting history, and a

romantic link with the Scotland of two hundred years ago. Tom

o’Shanter’s Cottage was built in 1837 as a small farm, holding about

six acres of the surrounding land. Its tenant in 1841 was Richard

Leay, a master stonemason and probably a Scotsman. It is likely that

Richard Leay carved the stone set in the gable end of the cottage, the

stone which gave the cottage its name. The stone depicts a scene from

the poem “Tam o’Shanter” by Robert Burns. In the poem, Tam was riding

home after a day at market, a little the worse for drink. The night

was dark and stormy, and on the way he disturbed a party of witches in

the old haunted Kirk of Alloway. The drunken Tam roared out “Weel

done, Cutty Sark” at the leader, and was immediately chased by the

witches. Tam managed to get across a bridge and the witches, who would not dare cross running water, caught the horse’s tail. Tam escaped, but “Poor Maggie” lost her tail: Now, do thy speedy utmost, Meg, And win the key—stane of the brig; There, at them, thou thy tail may toss, A running stream they dare na cross. But ere the key—stane she could make, The fient a tail she had to shake! For Nannie, far before the rest, Had upon noble Maggie prest, And flew at Tam wi' furious ettle; But little wist she Maggie’s mettle — Ae spring brought aff her master hale, But left behind her ain grey tail: The carlin caught her by the rump, And left poor Maggie scarce a stump! The cottage continued as a small farm for over a hundred years but, after being bumt down several times in the 1950s, was on the point of being demolished completely when the Birkenhead Historical Society, backed by the Council, stepped in with a scheme to restore it. With the help of local schools, organizations and individuals, Tam o’Shanter’s Cottage has been completely restored and is now a fully equipped field study centre. The annual rent on the cottage one pine cone is paid over to the Mayor of Wirral by the trustees each spring as part of a tradition which goes back to the days when squatters moved into the area. Another custom that of egg rolling — has recently been revived here too. Crowds gather on Easter Monday to roll gaily coloured hard—boiled eggs down the field in front of the cottage, the object being to get an egg into a hole cut in the turf at the foot of the slope. Egg rolling was popular in several parts of Wirral — the “bonks” of Birkenhead Park and Irby Hill were popular venues — and had its origin in the early days of Christianity,‘ the egg being regarded as a symbol of hope and resurrection. |

|

|

The

township of Bidston at one time covered an extensive area,

incorporating the parishes of Bidston, Claughton, Moreton and Saughall

Massie. The village itself is an architectural and historical gem

which, to the casual passerby, appears to have been preserved (not too

well) for looking at, but not for living in. hemmed in by a council

estate, a bypass and a steel mill, all erected within the last ten

years, Bidston village has changed surprisingly little over the years.

It was described in 1847 as “a little, quiet, grey village”,

words which still hold true today. Bidston’s peace has not, however,

been easily obtained. Up to the middle of the 1970s, all through

traffic between Birkenhead and Moreton had to pass through the

village’s main street. An endless stream of traffic, much of it

commercial, pounded the narrow, twisting road, shaking the

seventeenth-century foundations of the grey stone cottages along the

way and stretching the nerves of their twentieth century inhabitants.

After much pro-ing and con—ing, the Council at last recommended that

the village be by passed. |

| With its opening, the village has become virtually a backwater, for the only way out is into the housing estate at Ford. Much has been said and written about the disastrous planning (if indeed it can be called planning) which has resulted in he virtual destruction of Bidston’s immediate environment; suffice it to say that the damage has been done. It is to be hoped, though, that lessons have been learnt by many; not only by the local authority, but those ordinary folk of Wirral who should have done something, who should have stood up and shouted long and loud, to save Bidston from the ravishes of insensitive planning. Some did fight; as a result of a “Save Bidston” campaign in the late 1960s the Council declared the village the first Conservation Area in 1971. Yet even as I write, plans are afoot to convert one of the old cottages into a restaurant, and the Hall into a country club. (2015 - the Hall is a private residence, the restaurant never took place). |

|

|

But what’s all the fuss about, you ask. To

find out, let us take a closer look at the buildings in and about

Bidston village. Bidston Hall is set back from the main street along a

rough, sandy lane (2015 - now part of Eleanor Road). It is a grey

sandstone building, probably built about 1535, and rebuilt in 1620 by

William, sixth Earl of Derby, as a country seat of the colourful

Stanley family. James, who succeeded William in 1642, was a staunch

Royalist and during the Civil War fled to the Isle of Man where he

apparently succeeded in holding out against Cromwell. In 1649 Cromwell offered James a free pardon and the return of part of his surrendered estates if he would surrender the Isle of Man. ]ames’s reply was characteristic: Sir, I received your letter with indignation and scorn. I scorn your proffers, disdain your favour, and abhor your treason, and am so far from delivering up this Island to your advantage, that I will keep it to the utmost of my power to your destruction. Take this for your final answer and forbear any further solicitations, for if you trouble me with any more messages I will burn the paper and hang the bearer. ' Shortly after, leaming that Charles II was advancing from Scotland, ]ames rushed to England to join his monarch. He was captured at the Battle of Worcester, and was beheaded at Bolton a few days later. The last of the House of Stanley to live at Bidston Hall was Charles, the eighth Earl, and he lived there until 1653. Thirty years later the property passed to Sir Robert Vyner, the one time Lord Mayor of London and maker of the Coronation regalia, in whose family it remained for nearly 300 years. Today the Hall is a private dwelling, having been lovingly and painstakingly restored fifteen years ago from what was a virtual ruin. It is a romantic place, each niche telling a story; some say secret passages beneath the Hall connect with Mother Redcap’s old tavern, away across the once treacherous Moss in Waflasey. Hall Farm, just below the Hall, is, like the other farms in Bidston, a farm in name only, and the outbuildings are now used as stables. |

| Bidston’s parish church, St Oswald’s, stands dominating the village on a steep grassy bank. Evidence indicates that there has been a church of some sort here since the twelfth century, but the oldest part of the present building is the tower, early sixteenth century; the remainder was rebuilt in 1856 in a style similar to the previous church. Prominent amongst the heraldic shields above the west doorway is that of the Derby family, the three legs of Man. The church received its main support for a long time from Sir Edward and Lady Cust of Leasowe Castle. The arrival of the family for Sunday services must have been quite a sight, for it is recorded that they brought with them a retinue of castle servants, butler, footmen and maids! Before the rebuilding of the church in 1856, the roof was most likely thatched; the parish records frequently mention the “mowing and buying of rushes”. The reredos is a coloured glass mosaic by Salviati of Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper and is considered to be “one of the finest examples of Italian mosaic work in this country”. |

|

|

The fine grey stone buildings dotted about the village are worthy of close inspection. Immediately east of the church is The Lilacs (left) (formerly the Old Vicarage), built in the late seventeenth century, with its massive stone chimney-stacks. Nowadays our central heating with its attendant cleanliness is often taken for granted; the primitive method of cleaning these massive old chimneys makes entertaining reading: The method of sweeping chimneys adopted by the Bidston people in old days was to procure a good gorse bush, a long rope, and a brick or stone. A lad then climbed on to the roof and dropped the stone with the rope attached down the chimney, then the bush was pulled down two or three times until the chimney was clean. Unfortunately no provision was made for the catching of the soot, which descended in clouds and smothered everything with its sticky blackness. Attached to the house is the old Tithe Barn, a sturdy building with its thick walls and supporting buttresses. |

| Across the road from The Lilacs is Yew Tree Farm, half-timbered and dated 1697; and Church Farm, again seventeenth century. Church Farm is believed to have been an abbey or monastery and once housed a party of monks. It has traces of underground passageways or hides; and inside there are no less than thirteen different floor levels. |

|

|

Church Farm (and right) |

|

| At the top of School Lane, at the junction with the main street, is Stone Farm, originally the Ring o’ Bells Inn immortalized by Albert Smith in his book Christopher Tadpole. The inn was known far and wide as the “Ham and Eggs House”: At certain stated times, such as Easter, people came in crowds to consume ham and eggs. On such occasions the inn yard would be crowded with gigs, spring-carts and traps of every description. On one such day as an Easter Monday, during the 1860s, between thirty and forty hams, and a proportionate number of eggs, were polished off.Simon Croft, the inn’s landlord, was apparently quite a character; he erected a sign above the entrance: |

|

| Walk

in my friends and taste my beer and liquor; If your pockets be well stored you’ll find it comes the quicker; But for want of that has caused both grief and sorrow, Therefore you must pay today; I will trust tomorrow. |

Simon’s cellars. Simon, alas, was one of the inn’s best customers; he failed in his duty of keeping order over his customers to such an extent that it was common to see drunken men lying beneath the church wall on a Sunday morning. This apparently upset the churchgoers so much that they petitioned the squire to have the inn closed. This was carried out in 1868, and the village has been without an inn since. |

1945 Map |

The footpath from Bidston village along the lower westem side of Bidston Hill to Noctorum was, before the houses were built, a pleasant walk indeed, looking over the green valley of the Fender. The path still exists, but is now thoroughly suburban. It comes out at Ford Hill, at a tortuous hairpin bend on the Upton Road. For the walker, a steep, rugged path cuts across this bend; this ancient track, part of the old pack-horse route to Upton, is known locally as the “Pass of Thermopylae”; why, no one knows. Thermopylae Pass skirts the ground of Bidston Court, the original site of the house called Hill Bark which was removed and re-erected in Royden Park, Frankby; the old site here has been transformed into a pleasant public garden. A grand view of western wirral is to be had from here; the houses of the Fender Valley give way to the trees and fields of Arrowe, while in the distance the hills and mountains of North Wales form a purple backcloth. Here We are on the outskirts of Noctorum, “a spacious, leafy district of late Victorian houses, many very large and very red”. Much argument has raged over the origin of this unusual name; it is called Chenotrie in the Doomsday survey, and it has been said that this developed into its present form as follows: Chenoctre, Kenoctre, Knocktory, Knocktorum, and Noctorum. Chenotrie means “oak town”, this area being particularly noted as abounding in oak in earlier times. Another authority gives the place Celtic/ Gaelic origins: knock, being a hill, and torran a grave or tomb — the Doomsday Chenotrie being an error of the scribe. To add to the confu- sion, thirteenth—century documents show the place as ‘ ‘Knocttyrum”. There is no village. The higher parts of the suburb are extremely attractive; large houses with suitably large gardens off country-type lanes appeal as much today as they did a hundred years ago. The lower parts are, in contrast, unattractive; modern, high-density housing right up to the motorway. |

Water fountain:

http://www.firehydrant.org/pictures/glenfield-kennedy.html

http://www.archives.gla.ac.uk/collects/catalog/ugd/001-050/ugd005-pfv.html

Other Sites

http://visitbidston.blogspot.co.uk

http://brynjones.members.beeb.net/wastronhist/p_iroberts.html

http://www.seds.org/messier/xtra/Bios/roberts.html

http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/historic_figures/doodson_arthur.shtml

I also thoroughly recommend the books of Kenneth Burnley, local Historian and lover of all things on The Wirral